Tags

Anticipating the Next Wave of Fear

If 2025 marked a consolidation of horror as a serious critical form — a year of restraint, inheritance, and psychological rigor — then 2026 promises escalation of a different kind. Not louder, necessarily, but broader. The forthcoming slate suggests a genre increasingly preoccupied with systems: religion, legacy franchises, folklore, surveillance, bodily autonomy, and historical memory. Sequels coexist with reinventions; prestige auteurs collide with grindhouse traditions; and horror’s long-standing obsession with the past intensifies into something closer to cultural archaeology.

What follows is not a ranking of box-office potential, nor a speculative list of shocks, but a curated survey of the most critically promising horror films currently scheduled for 2026 — projects that suggest where the genre may be headed, formally and ideologically.

1. Untitled Jordan Peele Project

Jordan Peele’s continued absence of detail has become its own form of authorship. Since Get Out, Peele has positioned secrecy as a conceptual extension of his work — a refusal to allow audience expectation to pre-empt meaning. Whatever form his 2026 project takes, it is almost certain to engage with systems of power, visibility, and American myth-making, filtered through genre architecture.

Peele’s films operate less as allegory than as diagnosis, embedding social critique within meticulously constructed genre frameworks. Anticipation here is not rooted in premise but in method: the expectation that horror will once again be used to interrogate what America refuses to name.

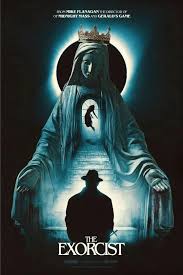

2. Untitled The Exorcist Project

Director: Mike Flanagan

Mike Flanagan’s involvement with The Exorcist franchise suggests a decisive tonal shift away from bombast and toward interiority. Flanagan’s strength has always been his ability to locate horror within grief, faith, and unresolved trauma — concerns deeply aligned with The Exorcist’s theological underpinnings.

With Scarlett Johansson and Jacobi Jupe attached, the project signals a focus on relational dynamics rather than spectacle. If successful, this could mark a rare revival: not of a franchise’s iconography, but of its existential seriousness.

3. The Mummy

Director: Lee Cronin

Expected April 17, 2026

Lee Cronin’s reinvention of The Mummy appears poised to reject colonial adventure tropes in favour of familial horror and bodily unease. The disappearance-and-return narrative frames the monster not as ancient spectacle, but as an invasive presence within the domestic sphere.

Cronin’s work has consistently emphasised corruption through intimacy — the idea that horror enters through love rather than conquest. This approach could finally liberate The Mummy from pastiche, reimagining it as a story of loss, identity, and irreversible change.

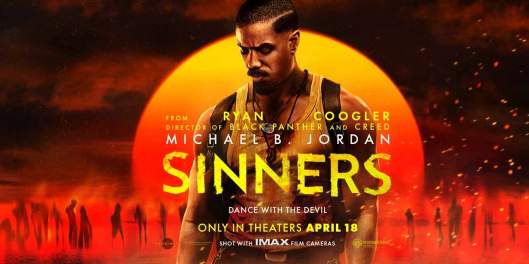

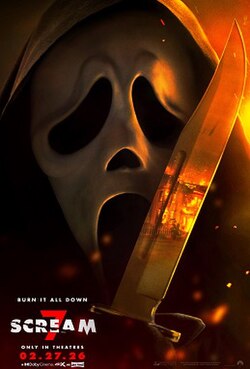

4. Scream 7

Director: Kevin Williamson

Releases February 27, 2026

With Kevin Williamson returning to direct, Scream 7 represents a rare case of a franchise turning inward rather than outward. The focus on Sidney Prescott’s daughter reframes the series’ meta-commentary as generational inheritance — asking what it means to pass trauma, notoriety, and survival forward.

Rather than parodying contemporary horror, Scream 7 appears positioned to interrogate its own legacy, transforming self-awareness into something closer to reckoning.

5. Terrifier 4

Director: Damien Leone

Expected October 1, 2026

By its fourth entry, Terrifier has evolved from cult provocation into a sustained endurance experiment. Leone’s commitment to practical effects and confrontational violence resists prestige horror’s current trend toward refinement.

What makes Terrifier 4 compelling is not escalation, but persistence. It exists as a countercurrent — forcing a conversation about the limits of spectatorship and the uneasy pleasure of excess.

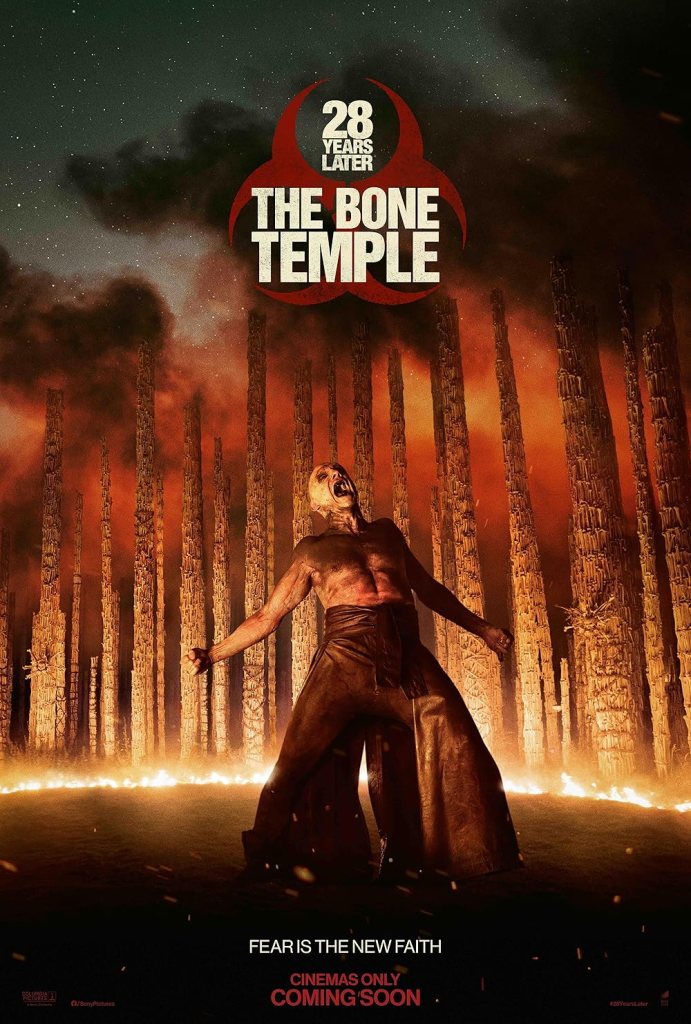

6. 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple

Director: Nia DaCosta

Releases January 16, 2026

Nia DaCosta’s entry into the 28 universe signals a shift from outbreak panic to post-collapse power structures. The move toward organised gangs and world-altering discovery suggests a franchise finally confronting its long-term implications.

DaCosta’s sensitivity to social hierarchy and myth-making positions The Bone Temple as less survival horror than political horror — a study of what replaces civilisation after fear becomes normalised.

7. Clayface

Director: James Watkins

Expected September 11, 2026

Clayface’s shape-shifting mythology offers fertile ground for horror rooted in identity instability. James Watkins’ involvement hints at a psychological approach rather than comic-book spectacle, reframing the character as tragic figure rather than villain.

The horror here is not transformation, but indeterminacy — the terror of never knowing where the self ends.

8. Evil Dead Burn

Director: Sébastien Vanicek

Expected July 24, 2026

With its plot under wraps, Evil Dead Burn remains one of the year’s most intriguing unknowns. Vanicek’s involvement suggests a grittier, more confrontational sensibility — potentially pushing the franchise toward nihilism rather than slapstick.

The challenge will be maintaining Evil Dead’s anarchic spirit while adapting it to contemporary horror’s more controlled brutality.

9. Ready or Not 2: Here I Come

Directors: Matt Bettinelli-Olpin & Tyler Gillett

Releases March 27, 2026

The sequel expands the first film’s class satire into something closer to mythic competition. By multiplying families and stakes, Here I Come risks dilution — but also offers the opportunity to transform satire into operatic cruelty.

If successful, it could become a dark fairy tale about inheritance, entitlement, and survival economics.

10. Werwulf

Director: Robert Eggers

Expected December 25, 2026

Eggers’ medieval werewolf film promises a return to folklore as lived belief rather than cinematic trope. Set against fog, superstition, and communal paranoia, Werwulf appears positioned as a study of fear as social contagion.

Eggers’ commitment to linguistic and historical authenticity suggests a film less concerned with transformation than with the terror of collective conviction.

11. Thread: An Insidious Tale

Director: Jeremy Slater

Expected August 21, 2026

Time travel as grief mechanism reframes the Insidious universe around consequence rather than shock. The central conceit — rewriting tragedy — situates horror within parental desperation and moral compromise.

If handled with restraint, this could become the franchise’s most emotionally coherent entry.

12. Wolf Creek: Legacy

Director: Sean Lahiff

Expected 2026

By shifting focus to children surviving in Mick Taylor’s territory, Legacy reframes the franchise around endurance rather than nihilism. The Australian landscape once again becomes indifferent, vast, and complicit.

The film’s success will hinge on its ability to balance brutality with perspective — horror as survival, not spectacle.

13. The Bride

Director: Maggie Gyllenhaal

Releases March 6, 2026

Gyllenhaal’s reinterpretation of Bride of Frankenstein foregrounds politics, gender, and radical transformation. Set against 1930s social upheaval, the film positions monstrosity as emancipatory rather than aberrant.

This is Frankenstein as social revolution — a reclamation of agency rather than a cautionary tale.

14. Resident Evil

Director: Zach Cregger

Expected September 18, 2026

Cregger’s involvement suggests a deliberate move away from franchise excess toward claustrophobic immediacy. A courier trapped in a hospital outbreak recalls survival horror’s roots: isolation, confusion, and bodily threat.

If successful, this could be the franchise’s first genuinely frightening reinvention.

15. Psycho Killer

Director: Gavin Polone

Releases February 20, 2026

Positioned as procedural horror, Psycho Killer explores violence through aftermath rather than spectacle. By centring a police officer navigating personal loss, the film aligns horror with grief and investigation rather than shock.

Its promise lies in restraint.

16. Victorian Psycho

Director: Zachary Wigon

Expected 2026

This gothic narrative of a governess amid disappearing staff evokes The Turn of the Screw through a feminist lens. Horror emerges gradually, through atmosphere and implication rather than revelation.

The film’s strength will lie in ambiguity: whether monstrosity is external, internal, or socially constructed.

17. Iron Lung

Director: Mark Fischbach

Releases January 30, 2026

Adapted from minimalist survival horror, Iron Lung translates isolation into cosmic dread. Its confined submarine setting and apocalyptic mythology suggest horror as existential endurance.

The challenge will be sustaining tension without relief — an experiment in atmospheric extremity.

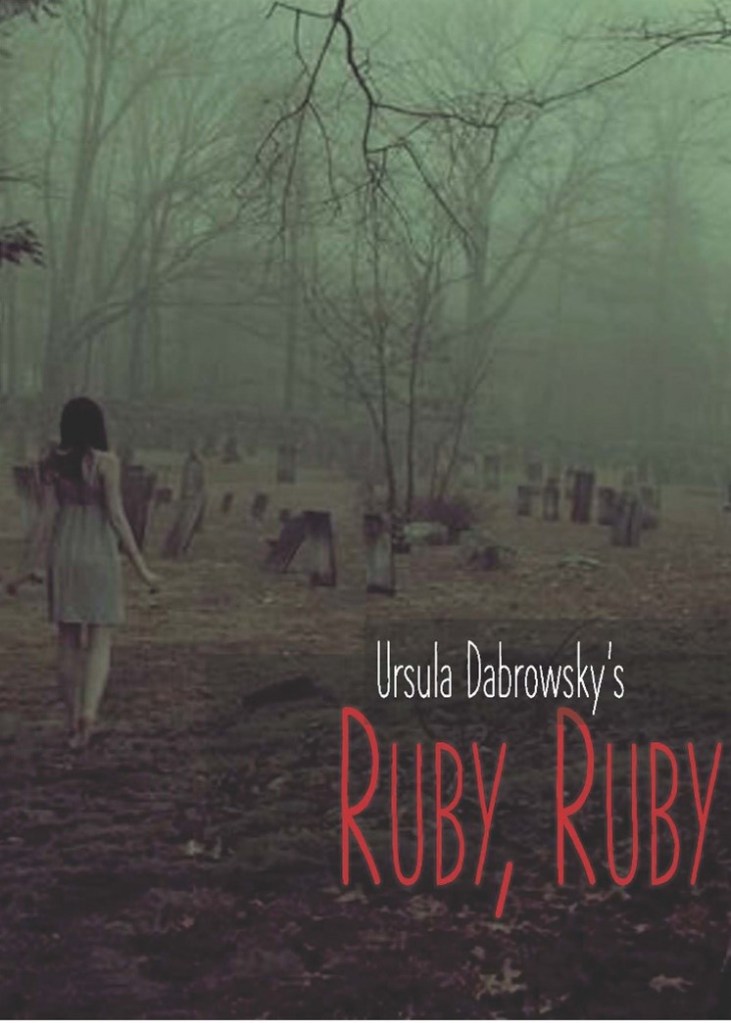

18. Ruby, Ruby

Director: Ursula Dabrowsky

Expected 2026

An Australian ghost story rooted in injustice and reclamation, Ruby, Ruby frames haunting as consequence rather than curse. The cemetery setting positions memory as a site of entrapment and resistance.

If handled with restraint, it could join the lineage of Australian horror that privileges melancholy over menace.

Closing Cut

The horror films of 2026 appear less concerned with novelty than with continuity — of trauma, myth, and unresolved systems. Whether through folklore, franchise, or speculative futures, these projects suggest a genre increasingly aware of its own history and responsibilities.

If 2025 taught us how horror cuts, 2026 may show us where it scars.

- Saul Muerte