Where shadows soar higher than the notes, and the arches echo with madness and music.

In the cavernous belly of the Palais Garnier, or rather its meticulously conjured phantom-double built on the Universal backlot, the silent Phantom of the Opera found its true cathedral—a place not of God, but of grotesquery, grandeur, and unrelenting gaze. For what is the Phantom’s lair, if not a sanctum sanctimonious of shattered beauty and compulsive longing?

Let us wander, as pilgrims through a fever dream, into the vast Gothic temple imagined by art director Ben Carré and production designer Charles D. Hall. A symphony of arches and shadows, their work was no mere recreation of Parisian opulence—it was a psychogeographic descent. An opera house turned labyrinth, a cathedral turned prison. Here, the verticality of Gothic design—spires, vaults, and vertiginous staircases—mirrors Erik’s own internal torment, reaching upward as he himself remains trapped below.

The architecture is storytelling in stone and plaster. The grand chandelier, both crown and executioner, becomes a symbol of suspended doom—until, like Icarus’ own sun, it falls. The Phantom’s subterranean realm, a gondola ride through the river Styx, contrasts wildly with the opulence above, reflecting the split psyche of a man who once longed to rise into the light but has become a ghost to the living world.

This set is no static background—it is character. It breathes. It swallows Christine. It trembles under the weight of Erik’s rage. It is built to oppress and awe, to reinforce the theme of duality: the sacred versus the profane, beauty versus deformity, the world above and the hell below.

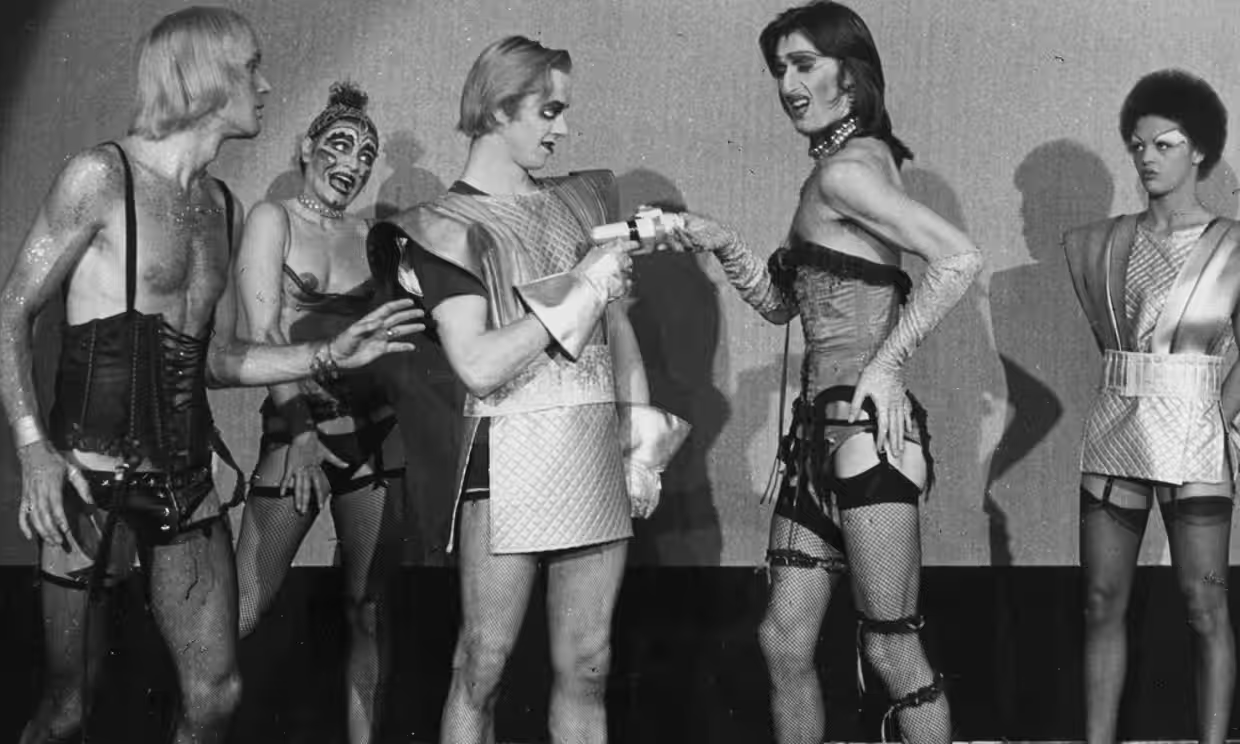

Indeed, the set design would influence Gothic horror cinema for generations. From James Whale’s Frankenstein laboratories to Hammer’s cryptic corridors, echoes of this opera house reverberate through time like an eternal organ chord. Even Andrew Lloyd Webber’s stage musical, in all its bombastic decadence, cannot resist homage—his falling chandelier and boat of dreams a direct inheritance from Julian’s silent blueprint.

And what of the symbolism? The opera house is society, masked and gilded. Erik, the phantom, is its consequence—an aberration bred from its basements. The corridors are arteries of repression. The mirror through which Christine vanishes is not an illusionist’s trick—it is a metaphor for entering the subconscious, for embracing what polite society denies.

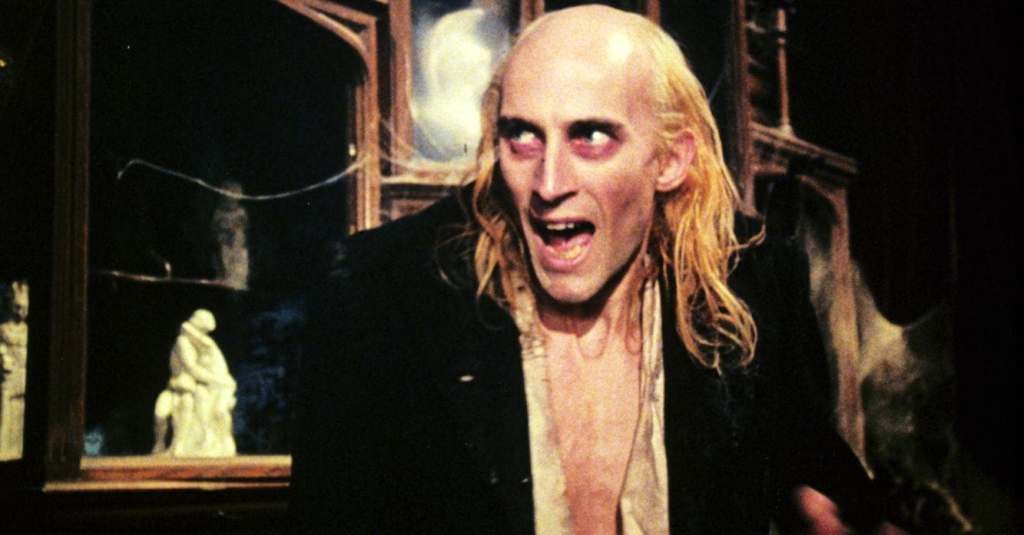

We watch the opera, and the opera watches us. It is voyeurism gilded in red velvet. And in Lon Chaney’s grim visage—revealed in a set piece that plays like a liturgical unmasking—we are reminded that all sacred spaces have their demons.

As one wanders through this haunted edifice, the sensation is clear: The Phantom of the Opera is not merely set in a gothic opera house. It is one.

- Saul Muerte