Tags

barry bostwick, jjim sharman, meatloaf, patricia quinn, richard obrien, susan sarandon, the rocky horror picture show, Tim Curry

Half a century ago, something strange, spectacular, and undeniably sexy burst out of the lab and onto cinema screens. The Rocky Horror Picture Show, directed by Jim Sharman and based on Richard O’Brien’s 1973 stage musical, was a box office flop upon release. But if you listen closely, you can still hear the echo of fishnets shuffling down the aisles, newspapers crinkling, and toast flying. What began as a gleefully campy homage to B-movies and rock ’n’ roll has become the longest-running theatrical release in film history — a cultural institution whose legacy transcends cinema.

From Stage to Screen

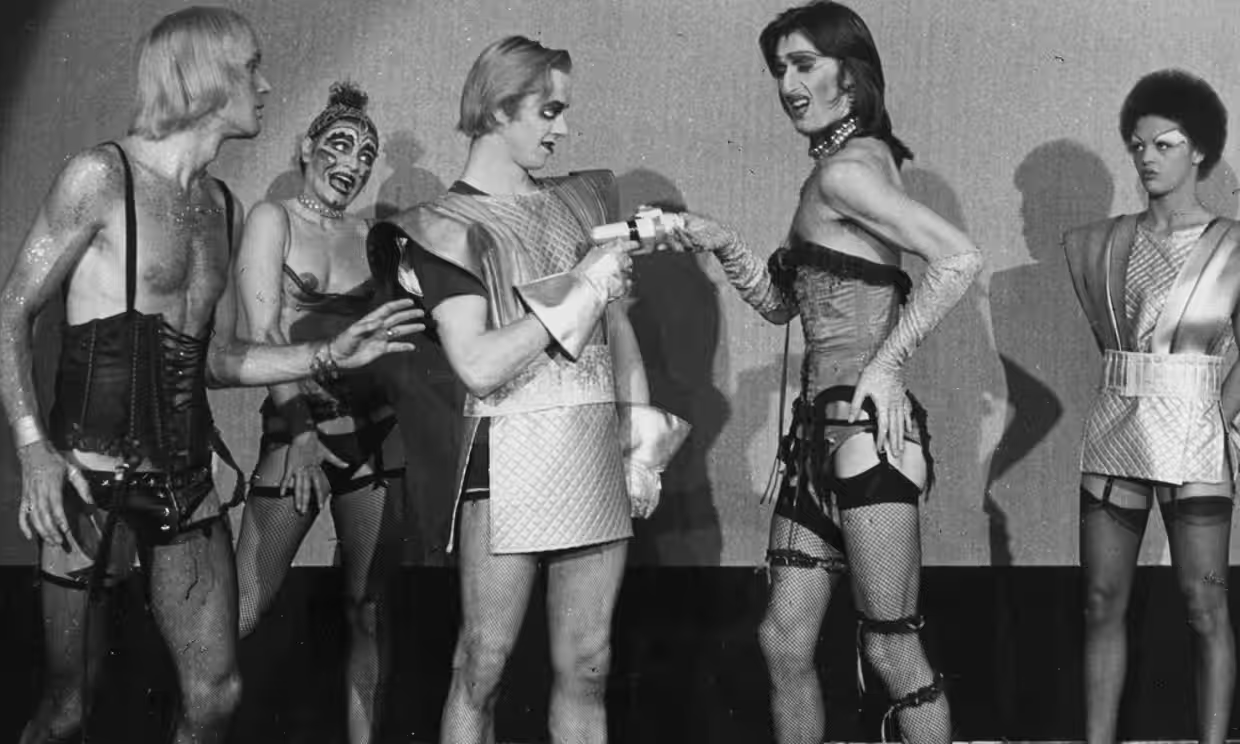

Before Rocky stormed the midnight movie circuit, it was The Rocky Horror Show, a West End stage sensation born in the countercultural crucible of early-’70s London. Created by Richard O’Brien, the musical combined sci-fi schlock, Hammer horror, and glam rock swagger into a tight, taboo-shattering stage production that quickly caught the eye of 20th Century Fox.

The leap to film in 1975 brought along director Jim Sharman and much of the original stage cast, including O’Brien himself. The film version expanded the show’s surrealism with expressionist sets and gaudy Technicolor palettes, but its heart remained the same: unapologetically queer, joyously anarchic, and deliriously fun. At its centre was Tim Curry’s legendary performance as Dr. Frank-N-Furter — a sexually fluid mad scientist from “transsexual Transylvania” — who made seduction, sass, and stilettos feel downright revolutionary.

Cult Status & Cultural Impact

The Rocky Horror Picture Show didn’t find its audience immediately. But beginning in 1976, it gained traction as a midnight movie, first in New York, then across the U.S. and worldwide. Fans came back week after week, dressed as their favourite characters, shouting lines at the screen, and participating in shadow casts — live performances synced with the film. It wasn’t just watching a movie; it was ritual, rebellion, and release.

Its impact can’t be overstated. Rocky Horror became a safe haven for outsiders, a beacon for the LGBTQ+ community long before mainstream media offered such visibility. It celebrated difference, queerness, camp, and kink with joyous abandon. Few films have made as many people feel seen by being so wonderfully strange.

Where Are They Now?

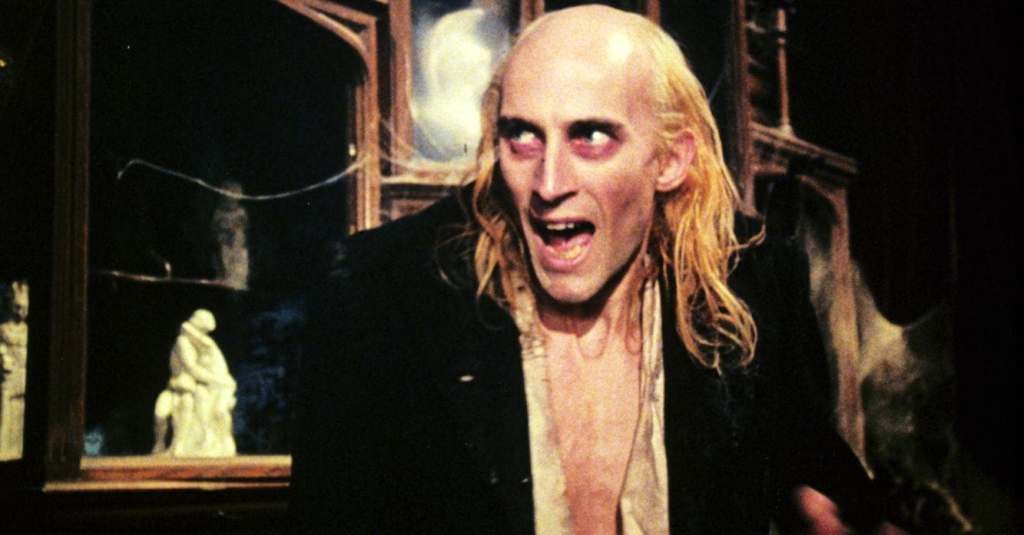

Tim Curry (Dr. Frank-N-Furter)

Curry’s outrageous performance launched a lifelong career. He went on to star in Clue (1985), Legend (1985), and as the terrifying Pennywise in the 1990 adaptation of It. After a stroke in 2012, he’s remained active in voice work and public appearances, still beloved by generations of fans.

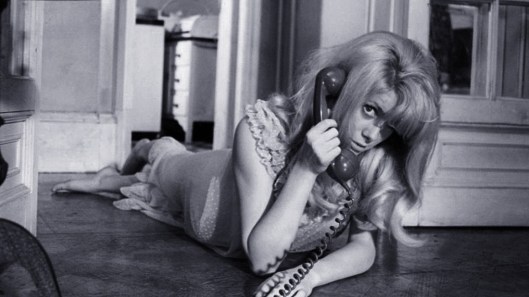

Susan Sarandon (Janet Weiss)

A relatively unknown actor at the time, Sarandon’s star rose fast. She would win an Oscar for Dead Man Walking (1995) and continues to be an outspoken activist and prolific performer.

Barry Bostwick (Brad Majors)

Bostwick built a steady TV and film career, including a long-running role on Spin City. He’s embraced his Rocky past, often appearing at conventions and reunions.

Richard O’Brien (Riff Raff / Writer)

O’Brien remained closely tied to Rocky Horror, penning Shock Treatment (1981), a spiritual sequel. He continues to act, perform, and advocate for trans rights, having come out as gender-fluid in recent years.

Patricia Quinn (Magenta)

Quinn has maintained a cult following and reprised her Rocky role in various fan events. Her distinctive voice still opens every screening with “Science Fiction / Double Feature.”

Meat Loaf (Eddie)

Already a rising rock star, Rocky helped launch Meat Loaf into the stratosphere. His Bat Out of Hell albums became massive hits. He passed away in 2022, leaving behind a legacy as larger-than-life as Eddie himself.

Nell Campbell (Columbia)

Credited as “Little Nell,” Campbell brought jittery energy and a killer tap number to the film. After Rocky, she pursued a career in music, releasing quirky singles and opening a beloved Manhattan nightclub, Nell’s, in the 1980s. Though she stepped back from acting, she remains a cult icon and pops up occasionally in retrospectives.

Charles Gray (The Criminologist)

Already a veteran of stage and screen before Rocky, Gray was known for his commanding voice and steely presence, having appeared in James Bond films like You Only Live Twice and Diamonds Are Forever. His role as the tongue-in-cheek narrator added gravitas and wry comedy to Rocky Horror. He passed away in 2000, leaving behind a legacy of charismatic authority and delicious deadpan.

Jim Sharman (Director)

Sharman continued to direct in theatre and film, but Rocky Horror remains his defining work. His vision helped translate the intimate chaos of the stage show into a cinematic spectacle that has never faded.

Still Sweet, Still Transgressive

Fifty years on, The Rocky Horror Picture Show remains electric. It may be a cultural artifact, but it’s never felt dusty. New generations continue to discover it, claim it, and dress up for midnight screenings. Its message — be yourself, loudly and without shame — is just as vital now as it was in 1975.

Whether you’re watching it for the first time or the five-hundredth, there’s always a reason to return to that spooky old castle. After all, like the man said — don’t dream it, be it.

- Saul Muerte