Top 10: The Undisputed Horrors of the Decade

#10. Blood and Black Lace (1964, dir. Mario Bava) ★★★★

With Blood and Black Lace, Mario Bava didn’t just craft a stylish horror film—he laid the foundation for the giallo genre and, by extension, the slasher films that would dominate decades later. The plot revolves around a masked killer targeting models at a high-end fashion house, but the real star is Bava’s camera. He bathes every murder in lush colour, surreal lighting, and baroque composition.

Beyond the violence, the film is a commentary on beauty, vanity, and objectification. It’s cold, glamorous, and entirely modern in tone. Bava strips away gothic frills and dives into something sleeker, bloodier, and more psychologically perverse. Its influence echoes in Argento, De Palma, and even Carpenter. As a blueprint for modern horror aesthetics, it’s utterly essential.

#9. Rosemary’s Baby (1968, dir. Roman Polanski) ★★★★½

Roman Polanski’s first Hollywood outing became a defining film of 1960s horror. Rosemary’s Baby is not just a satanic thriller—it’s a chilling portrayal of gaslighting, bodily autonomy, and the terror of maternity. Mia Farrow delivers a painfully vulnerable performance as Rosemary, who suspects her neighbours—and even her husband—of plotting to steal her unborn child.

The genius of Polanski’s direction lies in restraint. There are no jump scares, no overt monsters—just a creeping, invisible dread that builds as Rosemary’s reality collapses. Its depiction of conspiracy, control, and isolation remains just as terrifying in the modern age. Few horror films have captured such a profound sense of helplessness with such elegance.

#8. Persona (1966, dir. Ingmar Bergman) ★★★★½

While not a traditional horror film, Persona is one of the most disturbing explorations of identity, psychology, and emotional vampirism ever committed to screen. Bergman strips narrative to the bone, presenting a surreal, hypnotic story of a nurse and her mute patient whose identities begin to merge. Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson give performances of staggering depth and intensity.

The film bleeds horror through its stark visuals, experimental editing, and lingering dread. Persona is like a cinematic séance—haunting, elusive, and emotionally violent. It’s no surprise that directors like Lynch, Cronenberg, and Aronofsky count it as a key influence. It’s the horror of the self, the horror of losing who you are, and it still rattles cages today.

#7. The Innocents (1961, dir. Jack Clayton) ★★★★★

Adapted from Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, this elegantly executed ghost story remains one of the finest supernatural horror films ever made. Deborah Kerr plays a governess convinced that two children are being haunted—or are possibly possessed. Clayton’s direction is measured, deliberate, and psychologically loaded, and Freddie Francis’s cinematography is nothing short of sublime.

What makes The Innocents so powerful is its ambiguity. Are the ghosts real, or is it all in her mind? Kerr’s unraveling sanity, paired with the children’s eerie innocence, casts a spell of psychological dread. Every frame is composed like a nightmare you’re not sure you’ve woken from. This is gothic horror at its most refined.

#6. Night of the Living Dead (1968, dir. George A. Romero) ★★★★★

George A. Romero’s indie breakthrough redefined the horror landscape. Shot on a shoestring budget, Night of the Living Dead introduced the modern zombie and a new kind of horror—raw, political, and relentlessly bleak. A group of strangers barricade themselves in a farmhouse while the dead rise outside, but it’s the human conflict inside that proves even more devastating.

Beyond the gore and terror, Romero injected biting social commentary, particularly with the casting of Duane Jones as the pragmatic, heroic lead—a revolutionary choice in 1968. The ending remains one of the most shocking and cynical conclusions in film history. Romero didn’t just invent the zombie genre—he made horror dangerous again.

#5. Carnival of Souls (1962, dir. Herk Harvey) ★★★★★

Made on a meager budget by industrial filmmaker Herk Harvey, Carnival of Souls is a haunting, otherworldly descent into liminality and isolation. Candace Hilligoss plays Mary, a church organist who survives a car crash but begins to experience eerie visions and finds herself drawn to a decaying carnival pavilion. There’s something deeply off about everything, and that’s precisely the point.

The film exudes a dreamlike dread, feeling closer to a waking nightmare than traditional narrative cinema. Its grainy aesthetic, ghostly figures, and quiet existential despair place it closer to Eraserhead than any of its contemporaries. Forgotten for years, it’s now recognised as a minimalist masterpiece—an early taste of psychological horror that resonates far beyond its time.

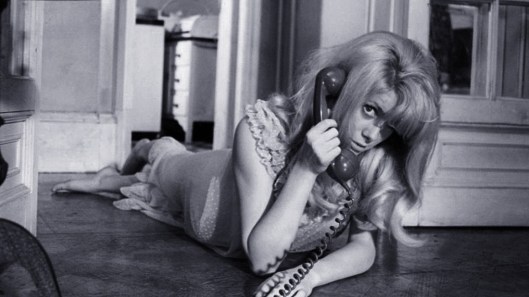

#4. Repulsion (1965, dir. Roman Polanski) ★★★★★

Roman Polanski’s first foray into English-language horror is a claustrophobic, harrowing portrait of mental breakdown. Catherine Deneuve plays Carol, a young woman whose aversion to men—and possibly her own sexuality—manifests in increasingly violent and surreal visions. Alone in her sister’s apartment, her mind begins to fracture, and the walls close in.

Polanski visualises psychosis with expressionistic flair: cracks in the wall pulse, hands emerge from shadows, and time slips into delirium. Repulsion is a deeply personal horror, terrifying because of how intimate it feels. It’s a study of trauma, repression, and psychological collapse, with Deneuve delivering a near-silent performance of devastating power.

#3. The Haunting (1963, dir. Robert Wise) ★★★★★

“The house was born bad.” So begins The Haunting, Robert Wise’s adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. A masterclass in suggestive horror, the film avoids special effects in favour of sound design, lighting, and psychological pressure. Julie Harris is unforgettable as Eleanor, a woman unmoored by grief, fear, and the lure of something malevolent within Hill House.

Wise builds tension through whispers, groans, and creeping camera movements, allowing the audience’s imagination to conjure the worst. It’s one of the finest haunted house films ever made—graceful, terrifying, and laced with subtext about repression, desire, and madness. The Haunting proves you don’t need to show horror—you just need to suggest it perfectly.

#2. Psycho (1960, dir. Alfred Hitchcock) ★★★★★

What more can be said about Psycho? With one shower scene, Hitchcock changed the face of horror forever. But the true genius of the film lies in its structure: the heroine dies halfway through, the killer hides in plain sight, and nothing is what it seems. Bernard Herrmann’s score screeches like a knife through the psyche, and Anthony Perkins redefined the horror villain with his portrayal of Norman Bates.

Psycho wasn’t just shocking—it was taboo-breaking, opening the door for horror to become a place for psychological complexity and transgression. It turned horror inward, focusing not on monsters, but on the terrors of the human mind. Its cultural impact is immeasurable, and it remains as nerve-shredding today as it was in 1960.

#1. Peeping Tom (1960, dir. Michael Powell) ★★★★★

Reviled upon release, Peeping Tom all but ended Michael Powell’s career—but time has revealed it as one of the boldest, most prescient horror films ever made. Carl Boehm plays Mark, a shy cinematographer who murders women with a camera rigged to capture their dying expressions. Powell confronts the audience with the guilt of voyeurism, turning the lens back on us.

Unlike Psycho, Peeping Tom makes us complicit. It asks uncomfortable questions about pleasure, violence, and cinema itself. Ahead of its time in style, theme, and psychology, the film paved the way for meta-horror and slasher films alike. Today, it stands tall not just as a horror classic—but as a cinematic reckoning. Disturbing, elegant, and unflinching, it is the defining scream of the 1960s.

Final Reflection: Shadows That Still Stretch

The 1960s were a decade of dualities. Horror clung to its gothic past while clawing toward a future of psychological disquiet and societal reflection. From the creaky castles of Hammer Horror to the nihilistic farmhouse in Night of the Living Dead, from Bava’s colour-saturated dreams to the stark terror of Repulsion, the genre evolved—sometimes subtly, sometimes violently—into a mirror for modern anxieties.

What’s most striking about revisiting these 60 films is how many of them still resonate. The fears they tap into—madness, loss, alienation, the monstrous unknown—remain timeless. In an era defined by political turbulence, social upheaval, and cultural rebellion, horror responded with a spectrum of expression: macabre wit, international surrealism, philosophical dread, and blood-soaked revolution.

These aren’t just entries on a list. They’re signposts of a genre learning to stretch its limbs, daring to question not just what frightens us, but why. The artistry of Persona, the invention of Carnival of Souls, the moral terror of Peeping Tom—they’ve all left fingerprints on the films that followed.

So whether you’re a long-time horror fan or a curious newcomer, the ’60s are well worth mining. They’re haunted by ghosts, yes—but also by bold ideas, aesthetic daring, and transgressive spirit. The shadows cast by these films still stretch long and deep.

Here’s to sixty screams—and many more still echoing.

- Saul Muerte